Jack Broughton is remembered both for his skill as a fighter and for the innovations he brought to the free-for-all fisticuffs that preceded modern boxing. In Broughton’s time, there were few standards of fair play. Bare-handed combat between two men was seen as a civilized advance over dueling with swords or guns, but “the manly art of boxing” was an anything-goes sport with no written code. Broughton came to realize, however, that a well-placed punch could often do more damage than some of the less refined gambits. More than any other fighter before him, Broughton saw the advantage of sizing up a rival and adjusting his methods to overcome a perceived weakness. In 1738, Broughton defeated George Taylor to win the title.

Broughton devised “Broughton’s Rules” in 1743, two years after he unintentionally killed ring opponent George Stevenson. While still allowing many avenues of attack, Broughton’s Rules introduced the now-familiar prohibition against hitting an “adversary when he is down,” banned all but the fighters and their seconds from the ring, and gave a downed man half a minute to get up. Broughton also invented “mufflers,” forerunners of modern boxing gloves, for use in training and exhibition matches.

Boxing was a popular diversion of the aristocratic class in the early eighteenth century, and like many early fighters, Broughton had a patron, the Duke of Cumberland. Cumberland abruptly withdrew his support, however, when Broughton lost the title to Jack Slack in 1750. The bout with Slack lasted only fourteen minutes because Broughton could not recover from a blinding punch. Boxing historian Pierce Egan reported that Cumberland had thousands of pounds riding on the match and pushed Broughton to fight on even after his eyes had swollen shut. He shouted accusatorially at his fighter, “What are you about, Broughton? You can’t fight! You’re beat!” According to Egan, the courageous Broughton replied, “I can’t see my man, your Highness; I am blind, but not beat; only let me be placed before my antagonist, and he shall not gain the day yet.” After this defeat, Broughton never fought again, and he turned his academy, a popular boxing arena, into a profitable antique shop.

Broughton, who lived to be 85 years old, was buried in Westminster Abbey in remembrance of his contribution to English boxing. He earned lasting recognition as “The Father of the English School of Boxing” and as the “Father of the Science of the Art of Self-Defense.” His rules survived for almost 100 years, to be superceded by the London Prize Ring Rules in 1838.

* * *

Excerpted with permission from 'The Boxing Register' by James B. Roberts and Alexander G. Skutt, copyright © 1999 by McBooks Press. All rights reserved.

Born: 1704

Died: Jan. 8, 1789

Induction: 1990

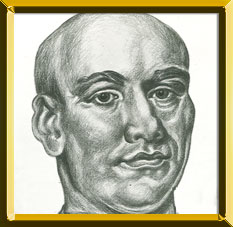

Jack Broughton